Learn more: Why is the Arctic melting and why is that a problem?

As a child, many of us hold the idea that the North Pole sits in the middle of a permanent whiteness. We don’t consider whether it’s a frozen ocean or solid land, we just visualise our world with its ever-present white cap. However, our quintessential view of the most northern reaches is changing, and these changes become more pronounced with every year that passes.

How is the Arctic changing?

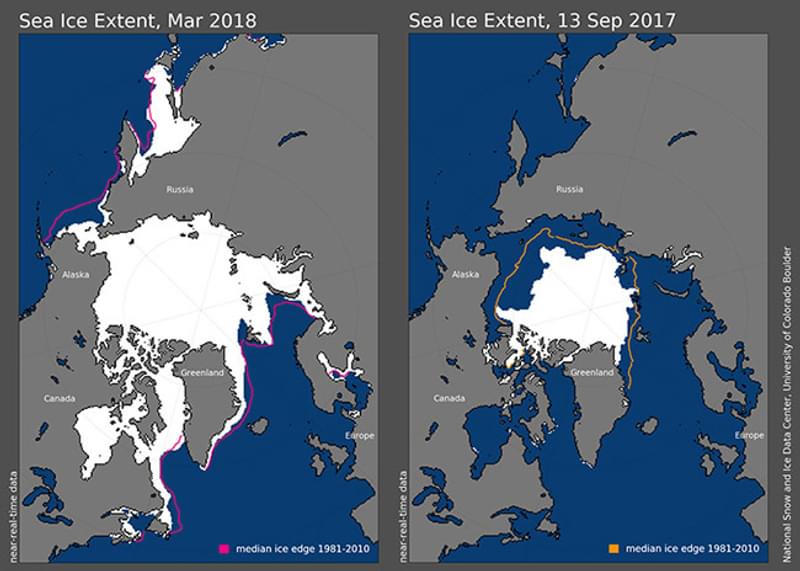

The area covered by ice has always fluctuated with the seasons. Sea ice forms, melts and reforms with the seasonal cycle natural in the Arctic, as shown in both figures 1 and 2.

NSIDC

NSIDC

NSIDC

NSIDC

The question is then, how is the Arctic changing over larger periods of time? In the seasonal cycle, whilst large quantities of sea ice melt in the summer, it didn’t disappear entirely (figure 1). However, the extent of the sea ice that forms every year is now decreasing; with 2012 marking the lowest extent of Arctic sea ice on record, and the years following showing little evidence of bucking this trend. Looking into the future, some climatologists estimate that the Arctic will be ice-free in the summer by 2036.

After centuries of trying to navigate the fabled North West Passage, this geographical shortcut connecting Europe and Asia may become a forgotten obsession. Instead ships will ply their trade across the entirety of the Arctic Ocean, rather than hugging the edges of land. This change has ramifications not just for international trade but also in terms of climate, habitat loss, natural resource exploitation and geopolitics, as well as the livelihood and culture of indigenous peoples who have long made the Arctic their home.

Does melting ice cause sea level rise?

The answer to this is both yes and no. Looking at some of the data, you would be forgiven for thinking that, considering the enormous area of the sea already not re-freezing in winter, sea level should have risen a lot more than the 55mm between 1992 and 2012. Either that, or the climatologists are seriously over egging their pudding.

Students are probably most familiar with the term ‘polar ice caps’ , this refers to all of the ice in the Arctic and Antarctic. However, here lies the crux of the matter: not all ice is created equal (see Learn more: All about ice). The most notable distinction in terms of sea level rise, is the source of the water from the millennia old ice sheets and the seasonal sea ice (figure 3):

- Sea ice forms seasonally from sea water, therefore it’s melting does not add ‘new’ water to the sea, and so will not cause significant sea level rise.

- Conversely, the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets formed from precipitation over millennia. Their melting would add significant levels of water to the sea. It’s estimated that if the Greenland ice sheet melted, sea level would rise by 6m; however this is small compared to the estimated 60m rise ensuing from the entire Antarctic ice sheet melting.

What other geochemical and physical problems could the changes cause?

The first is the reduction of the albedo effect. This is a cooling effect as a result of white ice reflecting solar energy. This effect is marked at the poles and helps maintain their temperature. However the loss of sea ice reduces the albedo effect, which results in more heat energy being absorbed by the darker ocean water (shown in figure 4), which in turn makes it harder for new sea ice to form: thus creating a positive feedback cycle.

Catlin Arctic Survey

Catlin Arctic Survey

The second is changes to the ocean conveyor belt that moves ocean water all around the globe. For more detail, see Learn more: Ocean circulation.

What biological problems can the changes cause?

The sea ice also provides important habitats to a plethora of organisms; from the microscopic life that inhabits the brine channels, to larger animals such as polar bears and ringed seals. The possibility of trophic cascades is discussed more in Learn more: Trophic cascades.

What are socio-geo-political issues surrounding the change?

Reduced sea ice not only represents opportunities for shipping, which could provide a lower carbon transport infrastructure between Europe and Asia, but also opens up new areas for natural resource exploration. The Guardian has produced an interactive map [1] of current endeavours. One current issue is whether the chemicals used to mitigate environmental damage from oil spills will work in such cold temperatures.

In terms of geopolitics, the Russian claims to the North Pole [2] are well-documented. Many countries bordering the Arctic are surveying the continental shelves, used as a marker for delineating territorial waters [3]. There was also evidence of increased military build-up in Resolute Bay in the Canadian Arctic in 2011 and the Danish Army patrols in Greenland [4] were featured in episode 6 of the excellent Frozen Planet series.

This move to bring the Arctic hinterland of Canada and Russia under further control and to increase commercial activity in the region has had a negative impact on the indigenous peoples living there.

Many of the Innu are still fighting to retain much of their traditional lifestyle, increasingly difficult as the government hands out their land in mining concessions, floods the heart of their territory for hydro power schemes, and builds roads which cut up the remainder. In April 1999, the UN Human Rights Committee described the situation of tribal peoples as ‘the most pressing issue facing Canadians’, and condemned Canada for ‘extinguishing’ aboriginal peoples’ rights.

Cross-curricular | Ages 7-11

Frozen Oceans

Based on journeys undertaken by real explorers and scientists, the Frozen Oceans (Primary) education programme is designed to introduce students to what life is like in the High Arctic.

Science | Ages 11-14

Frozen Oceans

The Frozen Oceans Science resources introduce working scientifically concepts and skills to 11-14-year-olds through enquiry-based lessons which replicate work done by field scientists in the Arctic.